While communicating the intended global audience for our project The Sari: A How-To Drape Film Series, a few North American well wishers asked: “are you planning to address cultural appropriation?” Truthfully we were not planning to, as we had not thought about it.

Indeed, it seems to be more of a question off India’s shores, as a survey Border&Fall conducted with over 50 men and 50 women in India indicated it was less of a concern. The overarching sentiment for 100% of women and 92% of men was that the sari may be worn by anyone who wishes to. The respondent’s comments imply an expansive outlook: ranging from, “A sari looks great on everyone, irrespective of their heritage”, “It should neither be imposed nor prohibited for anyone” to, “Just like Indian women wear Western clothes, it is quite OK for others to wear saris”.

Yet given the attention surrounding the subject of cultural appropriation globally, this is an opportunity to address our intentions and point of view on the subject and of course, encourage an open discussion.

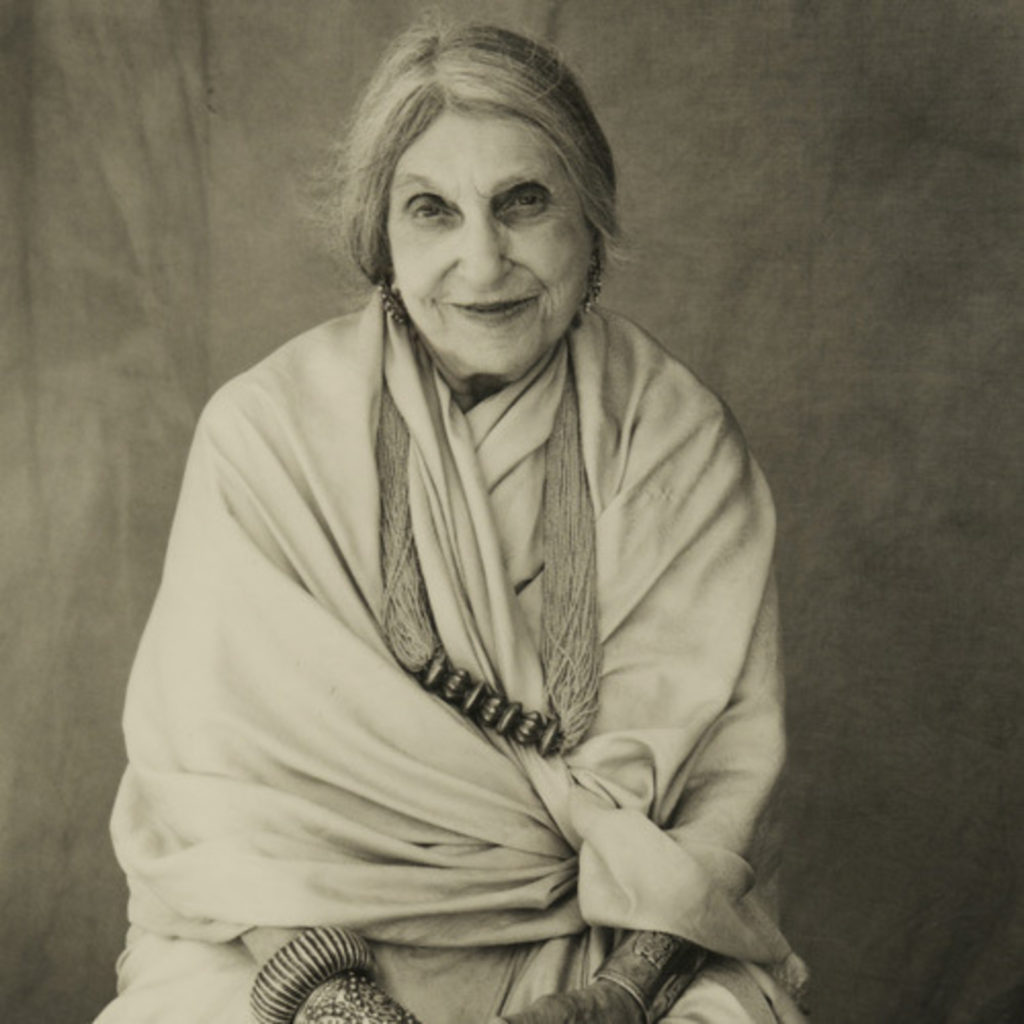

Above: Beatrice Wood, an American artist who integrated Eastern philosophy into her work and life. image | Tony Cunha

Entrenched in long-standing history that recent events have shifted into the spotlight, the ethics of cultural appropriation seem to touch a nerve on several fronts. Whether and how culture should be appropriated by those it doesn’t “belong” to infuriates, perplexes and inspires the source community, the creative who borrows or references and the ultimate audience or consumer at whom the work in question is aimed. “It’s most likely to be harmful when the source community is a minority group that has been oppressed or exploited in other ways or when the object of appropriation is particularly sensitive, e.g. sacred objects,” writes Susan Scafidi, author of Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law.1

The fact that, more and more, cultural appropriation is being thrown into the ring of identity politics only seems to propel the notion that there must be a side to take.

Miley Cyrus twerking onstage, hipster headdresses at music festivals and a kimono controversy at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts2 have brought forth opinions that run the spectrum. Last month, the Brisbane Writers Festival found itself scrambling to assuage the repercussions of a keynote speech by novelist Lionel Shriver who expressed her view that the fear of cultural appropriation was a significant threat to literature. An article in The New Yorker3, examining the considerable backlash Shriver received, pointed out: “A common lesson in every fight about cultural appropriation is that no one appears to be changing anyone else’s mind.”

Above: English supermodel Naomi Campbell on a trip to India, English actress Helen Mirren at the 2004 Primetime Emmy Awards

Articulating the nuances of each argument is a feat but an important step towards addressing some of the questions head on. For instance, how much weight to attribute to the power dynamic between dominant and minority groups? Should it matter whether the culture being appropriated continues to be marginalized? Does creating ‘safe spaces’ and tiptoeing around uncomfortable areas only perpetuate exoticism?

With India specifically, defending the ‘minority’ tag – given our significant population statistics and current economic power – is a bit of a stretch. As for undermining the sari’s sacredness, reservations from those who hesitate to wear one tend to be, “Is it religious?” (Answer: No), “Does one have to be married to wear it?” (No) and, “Is it meant to be worn only by Hindus?” (No). Perhaps this is overwhelmingly why Indians are not offended, and in fact, enjoy seeing others embrace the garment.

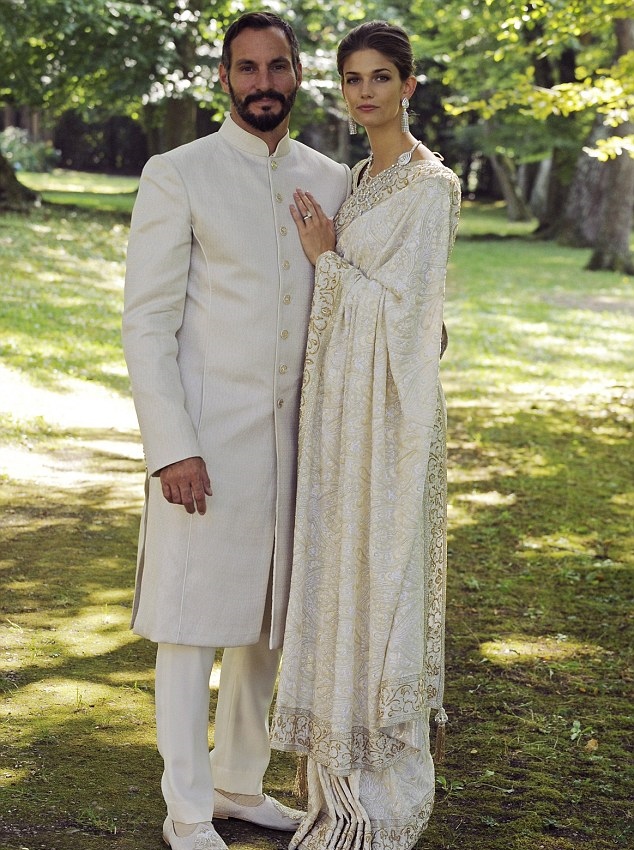

Above: Prince Rahim Aga Khan and American model Kendra Spears at their 2013 wedding in Switzerland image | Getty images

Speaking as a group actively concerned and involved in the developing aesthetics of India, we would be happy and proud if the sari were fully recognized across the globe for its genius design, versatility and relevance.

We’ve seen it contribute through textile and drape; why couldn’t it give itself as a complete garment for all to take pleasure in?

For us, the bigger question is how can we uninhibitedly, and still responsibly access, participate and celebrate all that is truly special and fascinating about living in such a diverse world? To that effect, we believe that appropriating with a fair degree of research, consult and sensitivity authenticates the intention. Making a legitimate connection with another culture through genuine interest, engagement and perhaps integration should prevent it from being misconstrued as a thoughtless or casual act. Whether one does it convincingly or not is always up for critique but to borrow Shriver’s use of a “modern cliche” to illustrate her point, the answer could be to “keep trying to fail better.”

Above: American actress Zooey Deschanel as Jess in the TV series ‘New Girl’ at her best friend’s wedding

Through news media and our personal interactions, we’ve noticed that cultural appropriation, when discussed in a climate of openness, can lead to empathy, education and a deliberate decision on how to proceed with a debated action. And equally how, when met with a hardened stance that won’t give an inch, the only thing opened is a can of worms.

This project takes the former approach, rooted in our larger belief that a culture of openness – to adaptation, preservation and multiple perspectives – is what builds and allows communities, and design, to thrive.

______________

1What Is Cultural Appropriation And Why Is It Wrong?

My only relation to the Indian culture is through the stories of my (English) Grandmother who worked in India for many years. I have been drawn to, and fascinated by the Sari for as long as I can remember. THis article was a great read and cemented what I understood regarding appropriation. I am attending a Bengali wedding this weekend and can’t wait to wear my Sari. I received so many complimets from so many women, Indian, Bengali, English, the last time I wore it and I feel fabulous when I wear it.It’s a work of art in its most simple and elaborate forms. THanks B&F.

Aimee – That’s so lovely to hear!

A ‘cultured’take on the topic, specially relevant today! Bravo!

Lovely post on sari ! Loved it 🙂

I loved this article! I am predominantly white with some North Indian heritage way back in my genealogy and have always resonated with Indian culture. I study raaga and teach yoga and it seemed completely natural that I should wear a sari for my wedding (my husband, who is German-American and Chinese, wore a kurta).

I have always felt that as long as I learn as much as I can about any traditions I may adapt and practice them authentically, with gratitude and with respect then I am actually helping to spread their influence wider and help hold them as living traditions on this earth.

I look forward to your film as there are so many ways to drape a sari-I would love to learn more!