Undoubtedly, the beauty of handmade textiles comes from their human element. Highly laborious and often simplistic when placed beside the 21st century factory production process, the age-old techniques reveal a mastery of skill and a result full of life and history. While there has always been a market for handmade goods, the market is changing along with the rest of the world and presents a new set of challenges to local artisans, especially with respect to globalization.

A traditional Ajrakh print, historically seen on a widow’s skirt in rural Gujarat, is now rendered on high-end bed sheets and retailed in New York department stores. Indigo-dyed cotton, which for millennia has been a means to regulate the body from intense desert heat, is now sewn into skin-tight garments on Parisian runways. The artisan is no longer making goods for his own community; instead, he sells to customers in faraway lands whose context he may not intuitively understand.

As a denim designer and developer for major brands in the United States, my work with international production facilities has been focused on hand work and individual garment personalization, but it did not cross over into traditional handcraft. Trips to Vietnam, Sri Lanka, China, Turkey, Mexico, Tunisia, and Colombia were for development of products made to my brand design and specifications, mainly injecting an aged and individualized feel that breathed life into new clothes.

I have spent a great deal of time travelling overseas and working with textile manufacturers during my career, but it is the first time I am encountering the question: how is the local artisan to evolve with a rapidly globalized market?

When I quit my job last fall to pursue my dream of travelling India, I had no inkling that my professional experiences would play a featuring role. I, like so many other tourists, envisioned a cast and scenery of master yogis, snow-capped Himalayas, dusty markets with cheeky vendors, bright colors and an entirely new bouquet of smells and textures. Yet, in the last eight months, as I uncovered each of these fantasies from Himachal to Kerala – I began to realize that the career I had supposedly put on hold is integral to my experience as a traveller. Constantly drawn to hand-altered textiles, I have found myself visiting weavers, dyers, and embellishers throughout the country. And keen to work with local artisans, I am continuously contemplating how they can best adapt to international customers without the infrastructure of large scale production.

The developing relationship between craft supply and market demand is affected by many factors, including access to raw materials, skills, human resources, technology, and market linkages. From my design and production perspective, innovation through technology seems to provide great access to meeting new market demands.

Whether it is a smartphone that allows better communication between local craftsmen and international buyer, or mechanized tools that facilitate faster production, the application of technology is already bringing new business to an old craft.

As I visited textile-oriented clusters and villages throughout India, a few examples of successful innovation stood out. The Buddha brothers in Ajrakhpur, Gujarat, for instance, have built their own drills to speed up their production process. It appeared that the younger generation groomed from an early age to take over their family business, were looking at the craft differently, and experimenting with technique. Their ingenuity impressed me and I started to wonder what comes next for these artisans. Of course, the hottest topic in manufacturing globally is 3D printing, and, while it seems worlds away from small artisanal fabric workshops, I was interested to explore a possible interaction of these two forms of printing. Developed centuries apart, could 3D and woodblock printing be combined in some form that would incorporate modernity while still respecting tradition?

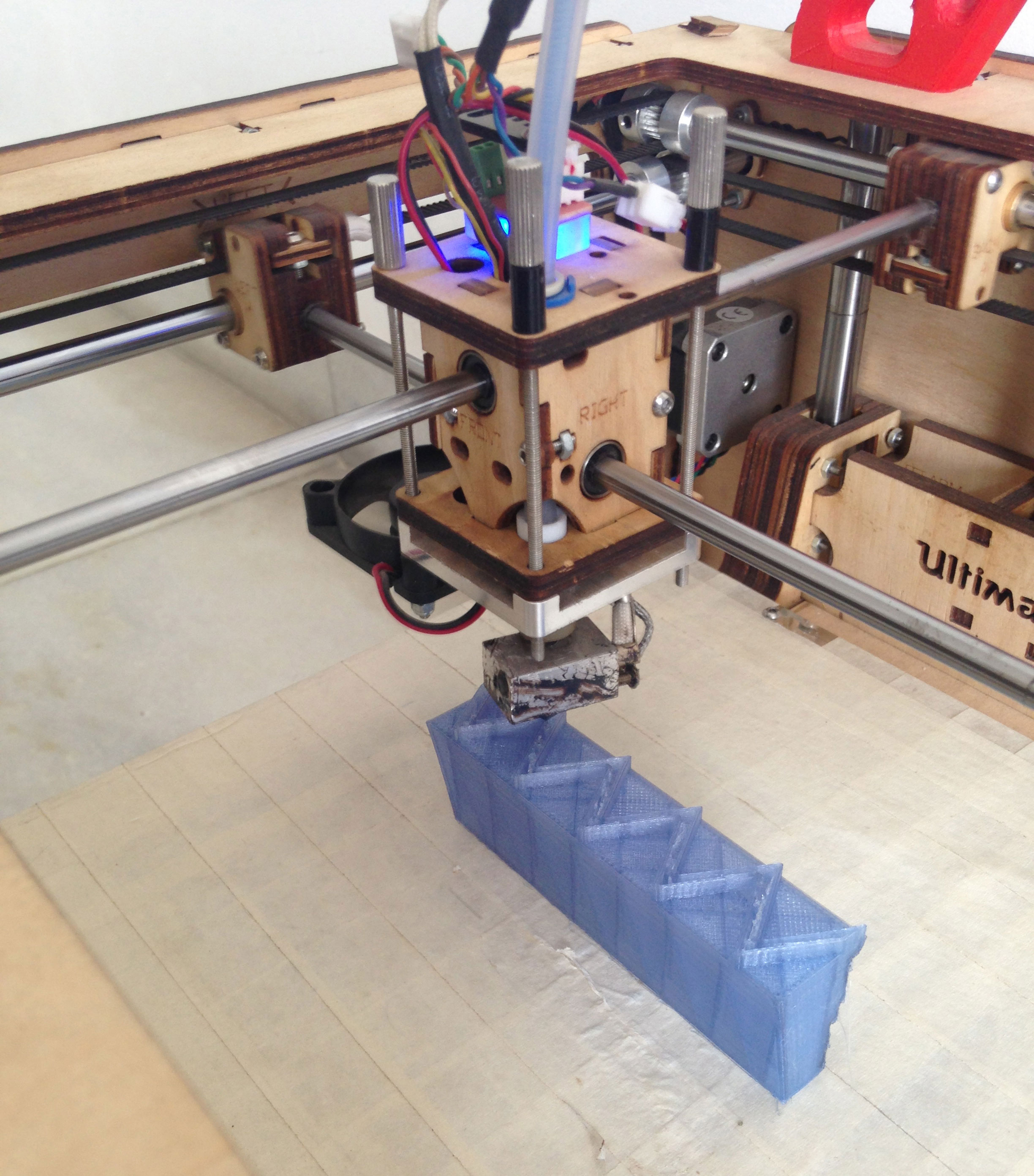

My residency at T.A.J. gave me some time and space to meditate and expand on this idea. I teamed up with Jaaga and their UltiMulti project, which helps socially responsible, purposeful makers prototype their ideas using a 3D printer. One of the most important aspects of my research is ensuring that the machine does not replace people, rather the people use the machine to create new products that were not achievable before.

What if traditional carvers had access to a 3D printer? What would they make? Could 3D printing help in productivity? Could it create new products? Could it eliminate waste? Could all this be done in a socially and economically beneficial context?

Tharangini is a family-run block printing studio in Bangalore run by Padmini Govind. Set amidst lush trees and employing the same skilled artisans for over 30 years, it is a serene creative oasis and the perfect place to explore new ideas. Padmini and I discussed the challenges facing block printers and block carvers, as well as those facing purveyors of traditional craft in general. She explained that it is getting increasingly difficult to find the level of skill hand carving requires that was available 50 years ago, as new generations tend to move away in search of “office” jobs. Another major challenge is updating the public perception of block printing. People tend to associate it with traditional simplistic motifs when in fact, it is possible to achieve quite complex designs. We decided that 3D printed blocks could be an interesting approach to resolving these issues, and began working on some prototypes to put the concept to the test.

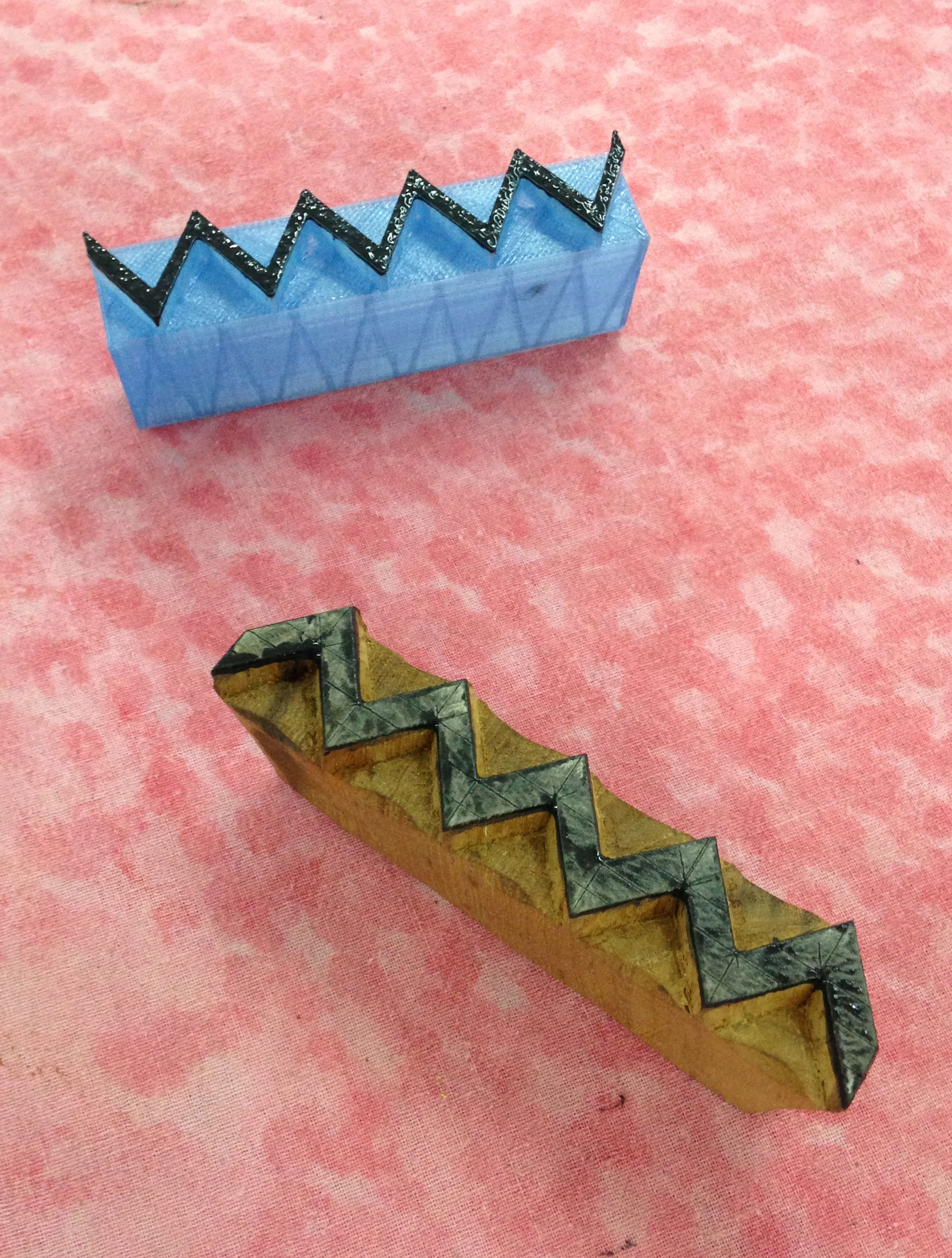

I decided to start from the very beginning and 3D print a basic wood block to see if it would work as a fabric printing substrate. I chose the traditional zig zag motif because it is iconic and simple, and visited Srirama, a skilled wood block carver outside of Bangalore to get the teak block carved. Then, I 3D modeled and printed a similar block so we could compare them side by side. Initial feedback was that the plastic surface was a bit slippery, both on the printing face and the holding grip, but we could alter the design to improve on those aspects. But overall, the 3D printed block worked!

With this knowledge in hand, I have started thinking about the next round of prototypes. Padmini showed me an incredibly finely carved block she had saved from the 70s (below) and explained how difficult it is to achieve that level of intricacy with carvers these days.

Perhaps 3D printed blocks could help supplement the current skillset of carvers? Further, how can I use this idea to make something modern and new rather than attempting to recreate the past?

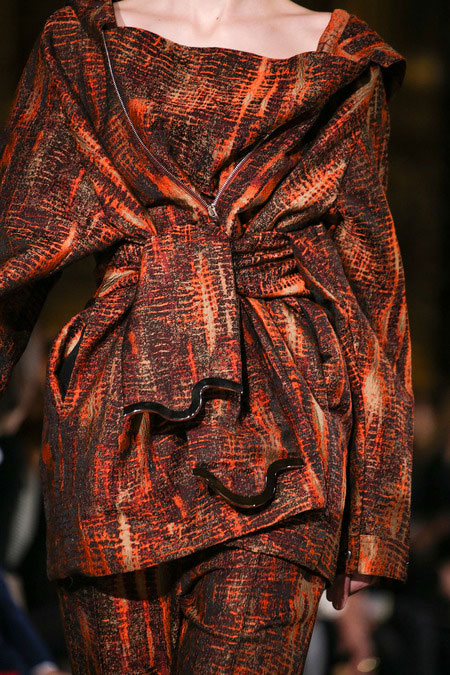

Looking at some recent digital prints shown on the runways by designers like Isabel Marant and Stella McCartney, I am inspired by the abstract motifs with fine organic shapes and detailing. For my next steps, I plan to utilize the intricacy potential of 3D printing by designing into contemporary abstract pattern trends. I would love to create an updated look for block printed fabric that maintains the signature human touch.

My explorations have made me sensitive to the questions and resistance that new technology invites. But while 3D printing is in its initial phases in the textile and apparel industries, we have already seen examples of its benefits in other fields. Medicine, for instance, has made great advances in prosthetics, employing Bioprinting to make functional organs such as ears.

Architects and engineers have started printing low cost, eco friendly housing in several countries.

When it comes to the handicraft sector, I imagine the resistance is because the public image of craft is closely tied with socio-cultural heritage. MIT Media Lab is doing some interesting work on the convergence of craft and 3D printing in the form of African basketry, which is a wonderful argument for repositioning this image into a more hybrid space. I believe we should nurture a new design plane that benefits from the coexistence of tradition and modernity.

The outcome of this research remains to be seen, and perhaps 3D printing will have little impact on the block printing world. Still, the livelihood of the artisan is undeniably changing and it is worth investigating all conceivable avenues to keep craft alive and flourishing. In doing so, we may succeed in ushering it into the cultural landscape that exists today, thereby bridging old with new, near with far, and tradition with innovation.

With considerable distance from my own apartment and the life I know in New York, the parallels to my personal path haven’t escaped me. As I round out my year in India and plan my own next steps, I feel particularly inspired by the way so many artisans approach unchartered territory. In a way I find myself in a similar position, evaluating what to hold onto from my background and what to let go of in the face of new inputs. And while this shedding can be scary and full of unknowns, my work with artisans has given me a fresh perspective on the nature of the process. The challenge is no longer about straddling two worlds – it is about integrating them into one that will shape what’s to come.

_________________

Becca Rosen is a New York based designer and textile developer with a penchant for texture and process. Having earned her degree in comparative religion from UCLA, she took an unconventional route to her design career and maintains a strong interest in cultural practice and traditional craft techniques. Becca worked for Marc Jacobs and Ralph Lauren among other New York designers for the past eight years and is currently taking a year to explore India.

This is a beautifully written article Becca and your work in inspiring. The thought of complementing the human crafts and not replacing is a benchmark and we need more people to think the way you do. Your research is thorough and I look forward to reading more about it!

Becca, good for you! I have been thinking about this topic for some time, as a blockprint specialist with soma blockprints in jaipur. Carving the blocks for collections within a production schedule is always a challenge. I had put aside the idea of 3d printing blocks as I know the material is too smooth and non-absorbent. our cherished blockmakers will not be abandoned, but an alternate system is worth developing.

i’d be interested to hear of any future developments and improvements to block making that you come across. perhaps we will meet while you are in india. safe travels