Innovation and technical evolution of craft is often considered a dilution of the authentic and traditional. I am uneasy with perceived dichotomies of traditional/modern, ethnic/contemporary, because they imply some judgment – traditional and ethnic is considered old or bad while modern and contemporary is believed to be good. Rather, tradition must be understood as living, growing and changing. Traditions always evolve appropriately to their socio-economic context, or they die.

In the craft-rich region of Kutch, Gujarat, evolution is exemplified in folk art traditions – crafts made for use within the artisans’ own world. I have also observed trends in Kutch crafts largely precipitated by external forces due to increasing production for commercial markets.

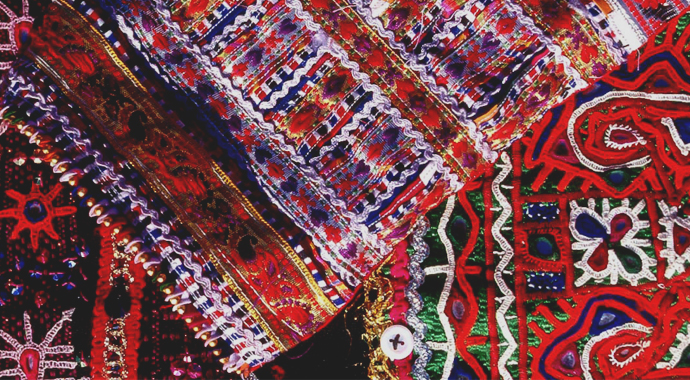

Fast Embroidery: the Rabaris of Kutch

Women of the nomadic Rabari community of Kutch have continued to embroider for their own use – for dowries and personal adornment. Their embroidery styles have changed dramatically over the four decades that I have been able to observe them. Each generation of Rabari women looks back and says, “embroidery is going to the dogs”, while the current generation is enthusiastically innovating according to their own strong, but entirely internal, sense of fashion (not much different from our “contemporary” world).

Artisans today welcome technical innovations—for the same reasons that we all do. In order to balance decreased time for hand work with increased demand for new fashions, in the late 1980s, women of the Kachhi subgroup of Rabaris invented an ingenious combination of machine and hand stitched embroidery.

Above: image | A Dhebaria Rabari woman embroidering

In 1995, The Dhebaria Rabari subgroup banned hand embroidery, deeming it “too expensive”. Dhebaria women responded by inventing another culturally permissible substitute: machine appliquéd ready-made ribbons, rickrack and trims. Both innovations opened the world of fashion for Rabari women. They maintained their aesthetic in new forms, which they themselves determined.

Artisans loved the new work because it saved time and they could innovate quickly.

With this evolution toward faster fashion most Rabaris now have very little interest, if any, in hand embroidery for themselves. As fashion trends change, increasingly rapidly, patience has dwindled and tastes have changed.

Technical Evolution of Craft: Living Rather than Languishing

For their own fashions, Rabaris chose to use sewing machines to save time and effort. Seeing this from a distance, people lament that what they perceive as a tradition is “dying” or “languishing.”

But the choices were independent, appropriate and elegant solutions to the shortage of time that artisans faced. We use computers rather than hand write, and many other technical time savers. Rabaris clearly expressed their values: they valued their aesthetic and their ability to remain creative directors over retaining old technology. I think when people don’t understand this, we have trouble.

When designers or NGOs come to the rescue and give young women printed patterns of older work, or work tenuously related to their traditions in order to “help” them get back on track, the young women are bored and do mediocre work. Not surprising, really. If, instead, we consider and value what the artisans are really interested in doing, that wonderful, ebullient traditional energy can be channeled positively.

In 2003, I asked Pabiben, a capable Dhebaria Rabari woman, to make a bag in the new “hari-jari” machine appliquéd ribbon style for me. I took it to the US and found that people really liked it. I dubbed it the “Pabi bag,” and we began to produce it. It was a bestseller for at least a decade. Today, Pabiben has her own business, complete with a website and Facebook page. And she is still selling very well.

Above: images | Pabiben, creator of the famous Pabi bags (featured on the right)

Market Driven Trends in Kutch Craft

Today most craft in Kutch is created for commercial markets rather than for the artisans themselves. This shift in focus has resulted in several trends directed by external forces.

Scaling-up > Market forces seek large scale production of hand craft. Besides the obvious economic advantage, there is an assumption underlying this trend, that the goal of craft is production on the largest scale possible. The assumption reflects the goals of the industrial age: faster, cheaper and more standard products – what machines were invented to make. I question the appropriateness of applying these goals to hand craft.

Companies dealing in craft pressure artisans to produce in the largest quantities imaginable. Those who can produce in scale have attained wealth and recognition.

To meet demands for huge quantities, they have employed artisans who don’t have the means to produce in scale as their workers. This has begun to create significant changes in the social structure. Within traditional societies, clients of artisans were hereditary and evenly distributed. Artisans were more or less equal in status and that was important to keeping society peaceful and balanced. But with major discrepancies in wealth and social status, we are beginning to see fissions, resentments and discontent.

Above: image | Pachan Premji Siju showcasing his collection of handwoven saris, stoles and shawls at Kala Umang, annual convocation and fashion show at Somaiya Kala Vidya. Image by Ketan Pomal

Superstar artisans > Traditionally, clients and artisans knew each other well. With focus on commercial markets, today, clients are distant and not so personally known. New clients contact economically stronger artisans who have been able to develop business networks. This client-driven network promotes those artisans to the extent that many people believe that there are only one or two weavers in Kutch, one or two block printers, one or two bandhani artisans, when in fact there are hundreds. This makes it difficult for smaller, newer artisans to reach new markets.

Conscious innovation by small-scale artisans > As a counteraction to the other two trends, smaller scale artisans have begun to consciously innovate in order to reach higher end new markets. I have been personally involved in this trend. Design education provided first by Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya and now by Somaiya Kala Vidya enables enterprising artisans to innovate effectively for chosen target markets. The Business and Management for Artisans (BMA) post-graduate course introduced by Somaiya Kala Vidya in 2014 furthers artisan capacity to create and market appropriate higher value, small scale production.

Above: image | Students of BMA master’s programme in a discussion with Vankar Shamji

As artisans learn design and business skills, not only does their work become more appealing to contemporary markets but in addition, their self confidence increases, enabling them to reach new markets successfully. Artisans learn to negotiate with clients; design graduates explain their conceptual and technical processes rather than bargain to lower prices. They strive to achieve more egalitarian communication with designers and clients.

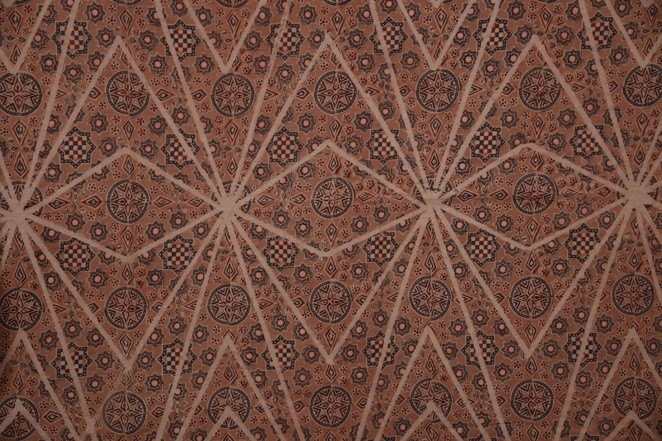

Above: images | Work of Alumni of Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya and Somaiya Kala Vidya respectively – Top: Khatri Aakib Ibrahim, block print, 2011. Bottom: Sohel Anwar Khatri, ajrakh print, BMA 2015

Design and business education, coupled with design innovations, also increase access to market contacts. Design graduates learn to use technology to support rather than supplant traditional hand production methods. Artisan designers use smart phones and social media to stay in touch with clients, rather than switching from hand to screen print, or from hand inserted woven patterns to jacquard looms.

As individual innovations on traditions have flourished, small production artisans have succeeded in reaching new markets, and markets have actually expanded. As one artisan said, “My income has increased ten-fold. But the Master artisan for whom I used to work has not suffered a bit.”

If we understand craft traditions as living and evolving, innovation is a clear prognosis for sustainability.

Judy Frater is the Founder-Director of Somaiya Kala Vidya, an institute for artisans’ education in Kutch, Gujarat. An Ashoka Fellow, she founded Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya and is a recipient of the Sir Misha Black Medal (2009) and Crafts Council of India Kamla award (2010). Frater has lived and worked in Kutch for over 25 years.

Border and Fall always delivers important information on the world of apparel making. Thank you for this incredibly enlightening article.

Interesting article and very informative.thanks !